30 years after the Chernobyl disaster it's shadow still lies heavy over Belarus. No other country was hit so hard. 70 percent of the radioactive fallout landed there, and one in five residents suddenly found themselves on poisoned land. Entire villages were buried in the ground to prevent people from returning. The disaster destroyed an entire rural culture.

|

| Chernobyl Radiation Warning Sign - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

|

| Text and Photo by Anna-Lena Laurén and Beatrice Lundborg |

The following text originally written by Journalist Anna-Lena Laurén have been translated from Swedish to English.

It is important to look for the apple trees. Where there's apple trees, there have once been a home.

Buried under the soil, overgrown with hazel bushes and newly planted pines.

The only thing that stands upright in this former village is a silver statue of a Soviet soldier, he stands at attention at the entrance as a kind of absurd symbol of a past buried under last year's dry leaves and pine plantations.

|

| Chernobyl Apple Trees - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Sometimes you find small hills in the countryside. There lies the demolished remains of a house. Or "chutar", as they say in these parts - a Belarus peasant cottage with spacious porch, worn stairs and ornate window frames.

I try to imagine how it once was out here. The cottages, barns, sheds. The sandy village road, which continues to the cemetery a short distance away. The graves are still there and every year villagers from Starinka gather there in early May to celebrate radunitsa, the Orthodox Church holiday when honoring their dead by eating and drinking on the grave yard. Sometimes even dance and sing to. Fistfights also occur. This is a region where the relationship with the ancestors and family's land is concrete and tangible, the ground and the trees are considered to be inspired, to leave them is like leaving a man. Not to speak of burying them.

"I'll tell you how our grandmother said goodbye to our house. She bowed to the barn. She went around and bowed to every apple tree. And when we left our home our grandfather took off his hat."

From: "Pray for Chernobyl" By Svetlana Aleksijevitj

In hundreds of Belarusian villages the farming community survived and remained well into the 1980s, despite the forced collectivization. Many had never left their home and among the elderly, it was still not unusual to not be able to read and write. April 26, 1986 catapulted this archaic society into the atomic age when the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded two hundred kilometers to the south.

The wind was blowing to the north and

70 per cent of the radioactive fallout ended up in Belarus, a country with more than ten million inhabitants. Over two million people were exposed to radioactive fallout,

over twenty percent of the country's territory were soiled. There was no other country than Belarus that was proportionally hit so hard by the Chernobyl disaster.

In the buried village of Starenka where we now are the measuring instruments, known as a dosimeters, are showing that the dose is 3.2 microsieverts per hour. As a comparison, the Japanese authorities after the Fukushima accident evacuated residents from areas with a radiation higher than 3.8 microsieverts per hour. In Sweden it is considered 0.1 to 0.3 microsieverts per hour to be normal background radiation. In Belarus levels seen at 0.2-0.4 are now normal, according to our local guide.

Starenka located in the so-called "zone", 600-kilometer-wide area affected by radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl disaster.

Here on the Belarusian side, where most of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is located a total of 70 villages have been buried.

The area is in turn subdivided into several zones. On the map it looks like a patchwork quilt. In the deep red zone, nothing appear at all, the radiation level is too high. In the red zone the levels are so high that no one is recommended stay there, but many have returned. In a third zone, the authorities have declared safe even when the radioactivity is elevated. The authorities say they monitor the situation. The fourth zone is located at the tip and have slightly elevated radioactivity.

|

| South Belarus Towns Deserted - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

"During the war, every fourth Belarusian died, today every fifth now live on contaminated land."

From: "Pray for Chernobyl" By Svetlana Aleksijevitj

Shortly after the disaster, thousands of evacuated people chose to move back to the zone. They simply could not stand to not live in their own homes and villages. One of those who from the beginning refused to move is 63-year-old Nina Perevalova that we found in the abandoned village of Dubna. Like many other older people who have chosen to stay in the empty villages, she believes that the evacuation was unnecessary.

|

| Nina Perevalova - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Everyone that left these parts have died. They were promised compensation and went away. They saw it as an opportunity to make money. But they were not happy in their new home and now most of them are dead. We who stayed are still alive on the other hand.

Nina Perevalova goes back and forth between the cabin and the hen house, cattle shed and pigsty. She's practically wearing galoshes, woolen sweater and a green jacket. Red plaid skirt, purple scarf on the head. Actually, she has no time to talk to us, she has chores to attend to and sticks hear head into the cabin and commands her husband to come outside.

|

| Nina Perevalova Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Kolja! Come out, we've got guests!

Mykola Nikitenko, 58, an unemployed tractor driver. Sometimes he works as a day laborer on construction sites, otherwise he lives off the garden, his pets and his wife's pension. He does not regret the decision to stay, even though they have been left alone in the village.

Here lived some fifty families before the disaster. We had a private shop and nearby there was a collective farm where a large part of the inhabitants worked. Over there was a road... and that's where one of his neighbors had his garden, Nikitenko said, pointing to an overgrown field.

|

| Mykola Nikitenko - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Of fifty households there remains only three. Four, five buildings remain, the rest ageing slowly but surely. Houses leaning and gray are the remains on both sides of the village road, they resemble old people who rely on a cane. The logs are gray with age, many houses have no roofs. Others have already fallen over and lies helpless on the ground, eventually becoming the piles of boards where people provide themselves with firewood.

The remaining houses have tin roofs that often goes almost to the ground. They look ancient, part of the landscape, brown and gray with beautiful, ornate window frames painted in bright green or sky blue. Nina Perevalovas and Mykola Nikitenkos house is simple, run-down and poor but impeccably well maintained - from the house to the roost to the pigsty and the sheep house is neat and tidy, everything has its place.

Birdsong sounds everywhere and hazel thicket have small green leaves. Up in a telephone pole there are birds. It is now spring, intense spring. Around one of the fallen houses small white and gray kids are leaping up and down of what is left of the timber wall. Nina Perevalova speak with them. She talks constantly with all their animals and calling them by name - pig named Vaska, the fearless gray hen Sivka and favorite price Gorka.

|

| Fallen Houses - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

This is my baby. Gorka, my little man .... Gorka my golden boy, says Nina Perevalova and scratches a kid area behind the ear.

Then she looks up.

I drink goat milk, gathering berries and mushrooms in the forest, growing in the kitchen garden. We have pigs and chickens. We are doing well. Only sore legs. Maybe it has to do with Chernobyl, what do I know? Everything was better and everyone was happier when we did not know anything about this radiation!

She invites us in the hall and pours fresh goat milk in a tin mug. I drink a sip, it tastes good. Then I set the cup back on the table. Our instruments have shown the normal radiation levels in this village, but I can not bring myself to drink up.

After reading about how tired these villagers are and other precautions I feel ashamed before Nina Perevalova, but she says nothing. By all accounts, she is accustomed.

When they last came here and measured how much radiation we have in the body, I had exceeded the norm. My husband had however completely normal levels. He drinks horilka (moonshine). It is said to be good against radiation.

|

| Natalia Krivosjejeva - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

"I want us to move. But my husband a lumberjack refuses."

A dozen kilometers further away is Sytjyn, another village which was evacuated after the disaster. A few years later, people began to move back and for two years life started to return and the village was rebuilt. But then it was emptied for the second time when unemployment drove people to move away. Today, all the houses are deserted - all but one with intense cobalt blue paint and a handrail made of birch trunks. It houses the unemployed postman Krivosjejeva Natalya, 40 years.

I was ten years old when they evacuated us to a neighboring village, Maksimovskij. But it never felt like home there.

The worst thing was not even the horrible, crude damp apartments, but we were shunned by locals. They called us "Chernobyltsi" and felt that we were a health risk. They did not talk to us. We had a serious food shortage in Belarus and they were furious at having to share the bread shipments with newcomers. Their disdain I will never forget, says Natalia Krivosjejeva and wipes away a tear.

Eight years after the evacuation, she returned as a newlywed to Sytjyn. The only thing which by then remained of the family's house was a bare stone base.

- The house had been newly built, it was valuable and was simply stolen, dismantled piece by piece. We moved into the empty library instead and I got a job as a postman in the neighboring village. But now my employment have been revoked and we are the last family who still live in this village. It's very sad to be a young person that does not have someone to talk to! I want us to move. But my husband is a lumberjack and refuses, Natalia regrets.

|

| Natalia Krivosjejeva - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

She is angry with herself because she and her husband have been waiting too long with the decision to leave.

All the other returnees have left our village. There are no buses here anymore, the line has been completely unprofitable. We can not afford a car, we can not even afford to have a pig for it needs food! We have no electricity or water, I wash clothes by hand. Look at my hands! says Natalia Krivosjejeva and holds out her rough hands.

Natalia does not think very much about the radiation. She and her husband live of their garden and self-catering, like most others in the zone. According to the dosimeters the radiation is at a normal level next to the house, but if you drive a few kilometers away then the radiation is significantly higher. Also, if you live in an area that is permitted in the zone, then some contaminated areas can lie next to you because the zones merge into one another.

|

| Dead towns - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

"They told us that we could drink the milk of our cows and eat vegetables that we grew. We did this for three years. Then they announced suddenly that we could not eat or drink anything."

Some seventy kilometers further away is a small community with the optimistic name Majsk. The houses there do not resemble the old Belarusian peasant cottages. They are white, modern two-story-straight rows, surrounded by square, fence enclosed gardens. Majsk is one of the villages that was rebuilt on a so-called safe area, which residents themselves scoff at.

Look how it's burning over there on the other side of the field. That area is radioactive, there we can not go. But every spring and summer fires occurs and the radioactivity spread. We must not go into the woods and pick berries and mushrooms. Everything is dangerous. We are completely surrounded by radioactive areas, we are like on an island. What life is that? exclaimed Olga, a thirty year old art teacher who is about to rake the yard.

Her mother glares angrily at us.

We have received orders not to speak to journalists! We are just to keep our mouths shut. I worked at the collective farm in the four years after the disaster.

I stood in the field and sowed and breathed in the dust, breathing in all that came out of the earth. Then it turned out that the area was one of the worst polluted by radiation and we moved here. Have we received any compensation? No. Because now we all live in a safe area!

She stops to rake and goes off furiously toward the potato patch behind the house.

All residents of Majsk originally came from a village named Tjudjany, an area the Soviet authorities first considered as safe. Therefore, the inhabitants were sent back home after the first evacuation, just four years later they were evacuated again to the newly built city Majsk - which turned out to be completely surrounded by radioactive soil.

They told us that we could drink the milk of our cows and eat vegetables that we grew. We did this for three years. But then they announced suddenly that we can't eat or drink anything. Clearly many are furious, but what good did it do? Now we live in an ill-chosen location, but what should we do? Where are we moving? Chernobyl has destroyed our lives, says Olga in the same tone as stated by many others I encounter.

People here often don't even regret it happened. They simply state it.

Olga say they have health problems, particularly pain in the joints. It's one symptom that is common among people who live in or near the radioactive zone.

But you can not prove that it has to do with Chernobyl. My children go to school here, they get iodine tablets, and free trips to a sanatorium twice a year. It's the only compensation we get to live next door to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, says Olga, who do not want to be photographed or say his real name.

On the other side of the field is a memorial with a small plaque:

"Here stood the village Tjudjany, with 137 families and 323 inhabitants. Buried in 1999. "

|

| Pavel Moisejev - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Our institute has absolutely no interest in concealing the presence of cancer, the opposite. We need all the resources we can get.

Thyroid cancer has soared in Belarus since the Chernobyl disaster. According to Pavel Moisejev leading the State Institute for Cancer Control in Belarus, the figures are quite clear. In 1990, the number of thyroid cancer cases in Belarus was 1.2 per 100 000 inhabitants, in 2014 it was 18.3. It is mainly children who are affected - and especially girls.

Large amounts of radioactive iodine was released into the atmosphere after the disaster. It affects the thyroid. For some reason, girls and women are more susceptible to radioactive contamination. We have not found an explanation for this. Luckily thyroid cancer is usually curable if detected in time, says Pavel Moisejev.

He receives us at the State Belarusian Center for Cancer Research located in Lesnoj, a leafy suburb of Minsk. Here is the

country's largest cancer hospital with 832 hospital beds, all of which are occupied when we visit the center. It is not only thyroid cancer that is increasing in Belarus - all forms of cancer has become more common. But according to Pavel Moisejev there is no scientific evidence of a Chernobyl connection, except in the specific case of thyroid cancer.

Moisejev is aware that many belarusians have stopped believing the authorities regarding Chernobyl. He raises his hands.

Guess if I constantly hear that ... I'm just saying what we on a scientific basis can establish! Our institute has absolutely no interest in concealing the presence of cancer, the opposite. We need all the resources we can get. Belarus is undergoing an economic crisis, but we have just built two new research centers and is building a new clinic. The construction will be completed, despite the fact that the state has much less money now. Today we have the resources in a completely different way than before. Our research is the best among all former Soviet countries.

While Moisejev notes that all diseases from Chernobyl's wake are still not known. As for metals like cesium and strontium with thirty years half life.

Radioactive iodine, cesium and strontium were released in large quantities. We do not yet know what consequences it can have - perhaps we'll know in 20, 30 or 50 years.

Only time will tell.

A person who has devoted his life to researching the consequences of the Chernobyl are Juryj Bandazjeŭski. He founded the country's first Chernobyl Institute in Gomel in 1989, one of the largest cities next to the so-called zone. Bandazeŭvski criticized the authorities for not taking the implications seriously and was jailed in 2001, accused of taking bribes from students. Amnesty International considered that the charges were fabricated and appointed Bandazjeŭski a prisoner of conscience.

Four years later he was released and Bandazjeŭski received temporary asylum in France. Today he is researching in Ukraine and I interview him on skype.

Since 2014, we examine children in two regions outside Kiev where there was radioactive fallout, Ivanovskij and Poleskij.

Every year we have investigated 4000 children aged between 3 and 17 years. Their general health is poor, 80 percent have various types of heart problems. The mortality in both heart disease and cancer is very high in this area, especially among young working-age people, says Bandazjeŭvski.

He would not comment on the situation in Belarus, because he can no longer work there. What he does want to make clear is that the EU - which admittedly is funding his research - have not taken the consequences of the Chernobyl seriously. Ukraine does not have the resources to invest in research and Belarus is a dictatorship, critical researchers run into major problems.

Research funding should be earmarked for each region and are not be given as lump sums to various authorities. Actually, there should in general not live any children in these areas. We can only imagine the long term effects on their health, and we need much more research. This requires, in turn, more resources to investigate each child individually and accurately determine which factors are interrelated, says Juryj Bandazjeŭski.

Accurate knowledge of how things fit together is something that Chernobyl disaster victims have pondered much over the past thirty years. At first they believed the authorities - which then turned out to lie systematically. Then they started to draw their own conclusions, which in turn led to hysterical rumors.

Today many victims fell a strong sense of still being deceived. They still do not know exactly how polluted the land is, or how sick they are. One only guess and wonder.

|

| Mykola Rasiuk and wife Valentina - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

Mykola Rasiuk was thirty years old when he drove along the road that is still called "Road of Death" - the road that led out from Pripyat, a model Soviet town next to Chernobyl in the current Ukraine. He drove past the nuclear power plant that was in flames. Above it hovered raspberry-colored clouds. People opened the windows, watched and admired.

When we arrived at the ferry a lot of fish had lost their ability to swim and floated up on the beach. People were fishing with their bare hands... no one understood how dangerous it was. We drove on to dacha and suddenly I was hit by a terrible headache. I stepped out of the car and vomited, and when we arrived, I drank a liter of vodka. Since then I have been living. But many of my friends and relatives are sick or dead, says Mykola Rasiuk.

His wife Valentina Rasiuk worked in a factory that made radios in Pripyat, Mykola worked as an electrician. Pripyat was founded next to the brand new Chernobyl nuclear power plant. It had been built in 1977 and was considered to be the safest in the world. When the accident occurred, very few understood that the whole area had become dangerous to live in.

I was worried for my relatives and friends who worked at the nuclear plant, that they had been injured during the accident. Not for one second I thought of the radiation. It was only when we came to the relatives of Kiev we understood what it was about. They said we would take iodine - something that we had not even heard of.

The authorities did not even tell us that the children should not play outside! said Valentina Rasiuk.

|

| Mykola Rasiuk - Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

From Ukraine the Rasiku family decided to move back to their home country Belarus.

When we got to Mogiljev people said to us that we had five years to live. How would you take it? I thought mostly about the children, I wished that the kids could grow up and become adults, says Valentina Rasiuk.

The children survived. By now the couple have lived in Mogiljev for over twenty years. Both their parents were however left in the so-called zone and died early.

Each anniversary of Chernobyl the city authorities make a speech. It's always about the same thing - the heroes who saved us from danger. Never about how many people got sick and died or had their lives ruined. I have requested the floor several times,

I have tried to share Svetlana Aleksijevitjs "Prayer for Chernobyl" - but they throw me out by force and now they won't even let me in at the memorial, said Mykola Rasiuk.

The State Institute for Cancer Research in Minsk says that it is not possible to establish any link between the Chernobyl disaster and any other cancer than thyroid cancer. Rasiuk just scoff when I say it.

We who have our roots in the zone have our own statistics. Every spring we go back to our home village to honor our dead on radunitsa. We meet, eat, drink and remember. We count how many are there and how many people have died. We look for ourselves what's really is going on.

Before the interview ends Rasiku pours Belarus balm, traditional herb liqueur in small crystal glasses. He raises his glass.

Cheers we are alive anyway.

|

| Photo by Beatrice Lundborg |

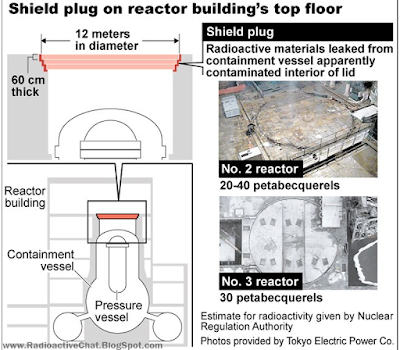

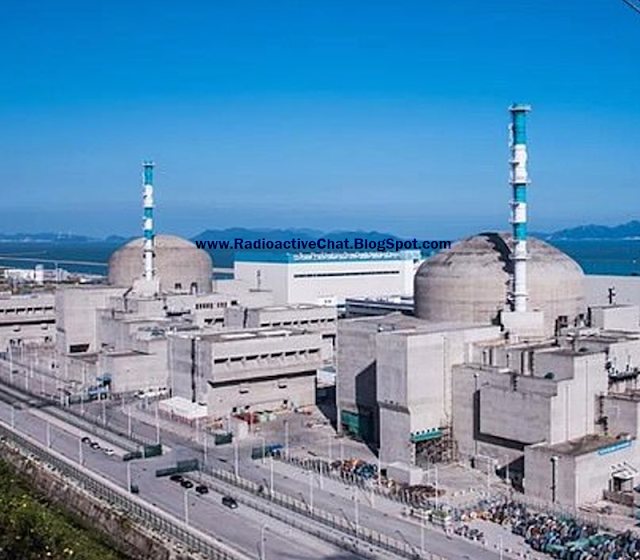

Taishan Nuclear Power Plant, in southern China, has been leaking radioactive gas for two weeks and is at risk of becoming a disaster, US intelligence agencies have privately warned

Taishan Nuclear Power Plant, in southern China, has been leaking radioactive gas for two weeks and is at risk of becoming a disaster, US intelligence agencies have privately warned The French firm which co-owns the plant (file image) warned US officials of the threat two weeks ago while asking for help to fix it

The French firm which co-owns the plant (file image) warned US officials of the threat two weeks ago while asking for help to fix it The Chinese state-run firm which owns the nuclear facility insisted in a report published on Sunday that everything is 'normal'

The Chinese state-run firm which owns the nuclear facility insisted in a report published on Sunday that everything is 'normal'